“There are about a dozen major environmental problems, all of them sufficiently serious that if we solved 11 of them and didn’t solve the 12th, whatever that 12th is, any could potentially do us in. Many of them have caused collapses of societies in the past, and soil problems are one of those dozen.” – Ward Chesworth of the University of Guelph, Ontario

***

The present administration is waging a war on drugs. President Rodrigo R. Duterte is hell bent on curbing, if not stopping, the proliferation of illegal drugs which have destroyed so many lives already.

But there is a kind of war that the government fails to engage itself. It’s an enemy that most Filipinos are aware of but no one seems to recognize it. It attacks on broad daylight and creeps at night when everyone is sleeping.

The adversary is not in the form of a human being but soil erosion. And because soil is less spectacular, media focused more their attention on on fossil fuel problems, climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity, logging and forest fires.

“Soil erosion is an enemy to any nation — far worse than any external enemy coming into a country and conquering it because erosion is an enemy you cannot see vividly,” pointed out Harold R. Watson, a former American agricultural missionary who worked as director of the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center (MBRLC) Foundation, Inc. in Kinuskusan, Bansalan, Davao del Sur. “It’s a slow creeping enemy that soon possesses the land.”

“Soil erosion is an enemy to any nation — far worse than any external enemy coming into a country and conquering it because erosion is an enemy you cannot see vividly,” pointed out Harold R. Watson, a former American agricultural missionary who worked as director of the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center (MBRLC) Foundation, Inc. in Kinuskusan, Bansalan, Davao del Sur. “It’s a slow creeping enemy that soon possesses the land.”

While experts talk about biotechnology, organic farming, high value crops, more crop production, and exportation, they fail to include soil – “the bridge between the inanimate and the living” – in the equation. After all, it has been estimated that more than 99 per cent of the world’s food comes from the soil.

“Without soil, there would be no food apart from what the rivers and the seas can provide,” said Edouard Saouma, former head of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). “The soil is the world’s most precious natural resource. Yet, it is not valued as it should be. Gold, oil, minerals and precious stones command prices which have led us to treat soil as mere dirt.”

Without soil, food security will always be an issue. Hunger is present all the time and peace and stability are but just dreams. “If the soil is not well cared for, a county can never develop a sound agricultural base. And without that, national development plans rarely succeed,” the United Nations food agency reminds.

But farmers themselves never consider soil erosion as an opponent in crop production. The story of Manong Doming is a representation of most farmers living in the uplands, which account 60% of the country’s total land area of 30 million hectares.

“At first, everything was just fine,” Manong Doming recalled. “We had enough and almost everything was affordable. We practice kaingin (slash-and-burn farming). Land was fertile and the use fertilizer was unknown to us then.”

“At first, everything was just fine,” Manong Doming recalled. “We had enough and almost everything was affordable. We practice kaingin (slash-and-burn farming). Land was fertile and the use fertilizer was unknown to us then.”

This was in the 1960s when his family moved to the hinterland near Mount Apo, the country’s highest peak. But as the years went by, he noticed something was not right in the method of farming he used.

Manong Doming observed that the produce from the farm considerably declined. This was evident in the corn he was planting. Over a period of 10 years, the corn production had dropped from 3.5 tons per hectare to only half ton.

But it was not only corn that was affected. Yields of other crops like banana, coffee, coconut and even fruit trees had also decreased by more than 50% over the same period. “Whatever happened?” he wondered.

To augment his production, Manong Doming started using fertilizer. He also used seeds of improved varieties of corn and other crops. To eliminate pests and diseases attacking his crops, he sprayed them with pesticides.

But despite all those efforts, crop production was still low. Together with other farmers in the area who were experiencing the same problem went to the MBRLC to find some possible solutions.

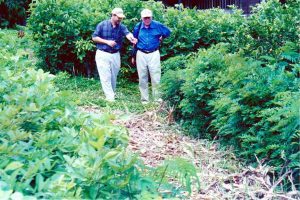

Watson and his Filipino staff talked with them. Hearing the farmers shared their woes and the solutions they tried to apply, the MBRLC experts visited the farms. In all visited farms, they observed one common thing: soil erosion.

According to Watson, once the fields are devoid of topsoil, the productivity of every farm will always be low – and the farmers won’t earn enough to meet their basic needs. “Soil is made by God and put here for man to use, not for one generation but forever,” he said. “It takes thousands of years to build one inch of topsoil but only one good strong rain to remove one inch from unprotected soil on the slopes of mountains.”

Lester R. Brown and Edward C. Wolf, authors of Soil Erosion: Quiet Crisis in the World Economy, further explained the consequences of soil erosion in food production: “The loss of topsoil affects the ability to grow food in two ways. It reduces the inherent productivity of land, both through the loss of nutrients and degradation of the physical structure.

“It also increases the costs of food production. When farmers lose topsoil, they may increase land productivity by substituting energy in the form of fertilizer. Hence, farmers losing topsoil may experience either a loss in land productivity or a rise in costs of agricultural inputs. And if the productivity drops too low or agricultural costs rise too high, farmers are forced to abandon their land.”

In the humid tropics, starting from a sandy base, a soil can be formed in as little as 200 years, experts said. But the process normally takes far longer. Under most conditions, soil is formed at a rate of one centimeter every 100 to 400 years, and it takes 3,000 to 12,000 years to build enough soil to form productive land.

But what nature takes a very long time to form could be washed away in 20 minutes or less by just one heavy rainfall in areas where the farmers don’t use the land carefully.

In a position paper in 1991, then environment official Victor O. Ramos said that denuded forest land experience 100 tons of soil loss per hectare in contrast to less than 8 tons per hectare per year from natural forests. Slash-and-burn farming, which most uplanders practice, has an erosion rate of 300-400 tons per hectare per year.

Once the topsoil is lost, it is lost forever. “No other soil phenomenon is more destructive than is soil erosion,” wrote Nyle C. Brady in his book, The Nature and Properties of Soil. “It involves losing water and plant nutrients at rates far higher than those occurring through leaching. More tragically, however, it can result in the loss of the entire soil. Erosion is serious in all climates, since wind as well as water can be the agent of removal.”

Soil erosion is nothing new. Archaeological sites of civilizations, studies showed, were undermined by soil erosion. The fertile wheat-growing lands that made North Africa the granary of the Roman Empire are now largely desert. The lowlands of Guatemala that once nourished a thriving Mayan culture were drained of their fertility by soil erosion.

“Societies in the past had collapsed or disappeared because of soil problems,” wrote Tim Radford, science editor at The Guardian. Quoting Ward Chesworth of the University of Guelph, Ontario, he further wrote: “Easter Island in the Pacific was a famous example. Ninety per cent of the people died because of deforestation, erosion and soil depletion. Society ended up in cannibalism, the government was overthrown and people began pulling down each other’s statues, so that is pretty serious.”

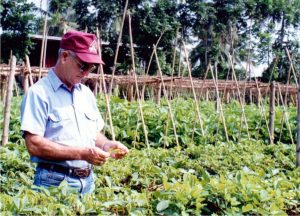

Watson and his Filipino staff knew it well. That was the reason why they came up with a sustainable farming scheme called Sloping Agricultural Land Technology (SALT). “SALT is a packaged technology of soil conservation and food production that integrates several conservation measures in just one setting,” said Roy C. Alimoane, the current MBRLC director.

“Basically, the SALT method involves planting of field and permanent crops in 3-5 meter bands between double-contoured rows of nitrogen fixing shrubs and trees (examples: ipil-ipil, kakawate and introduced species such as Flemingia macrophylla and Desmodium rensonii) to minimize soil erosion,” Alimoane explains.

Permanent and agricultural crops are planted all over the farm. Permanent crops refer to cacao, coffee, banana, citrus and fruit trees. Among the recommended crops are vegetables, cereals, and legumes.

In SALT, crop rotation is being implemented. For instance, those strips planted with cereals (corn or upland rice) earlier are planted with peanuts or winged beans in the next cropping. “Crop rotation helps to preserve the regenerative properties of the soil and avoid the problems of infertility typical of traditional agricultural practices,” Alimoane says.

Multistory cropping may also be practiced (planting black pepper, corn, and lanzones together in one hedge). In waterlogged areas, gabi, kangkong and other water-loving crops are planted. “We all do these to make use of all the available spaces of the farm,” Alimoane says.

“Some of the crops should be planted to feed the farmer’s family, while other crops are grown for sale, so family income is well spread out over the season,” says Alimoane. “Every week or every month, there’s always something to harvest. The system can, in fact, raise the family income threefold.”

But what makes SALT environment-friendly is that it helps in the establishment of a stable ecosystem. The double hedgerows of leguminous shrubs and trees between the land strips where crops are planted help conserve water and soil. The hedgerows, when cut every 30-45 days and incorporated back into the soil, improve its fertility and serve as mulching materials.

A study conducted at the MBRL C farm showed that a farm tilled in the traditional manner erodes at the rate of 1,163.4 metric tons per hectare per year. In comparison, a SALT farm erodes at the rate of only 20.1 metric tons per hectare pear year.

“The rate of soil loss in a SALT farm is 3.4 metric tons per hectare per year, which is within the tolerable range,” Alimoane claims. “Most soil scientists place acceptable soil loss limits for tropical countries like the Philippines within the range of 10 to 12 metric tons per hectare per year.”

The non-SALT farm, on the other hand, has an annual soil rate of 194.3 metric tons per hectare per year.

“The decline of our soils is a chronic, slow process without the urgency of other environmental crises,” declares Priscilla Grew, former director of the US Department of Conservation for the State of California. “Yet, soil is the basis for our very existence. Where it is lost, civilization goes with it.”