Jethro P. Adang is a little bit worried. The corns are already flowering. The ampalaya seedlings had been transplanted in the field two weeks ago. The water in the tilapia ponds is receding. The grasses have turned from green to brown. Last year, although summer was just around the corner, there was still plenty of water.

Adang is the new director of the Mindanao Baptist Rural Life Center (MBRLC) Foundation, Inc. He assumed the post last December yet when Roy C. Alimoane retired as the head of the non-government organization based in barangay Kinuskusan of Bansalan, Davao del Sur.

“We really don’t know what will happen to the crops we have planted,” he said. “Since I am still new here, I have told our staff to make some drastic changes with our cropping plans. After all, a dry spell is expected to hit the country as the weather bureau announced last year that a moderate El Niño will be felt all over the country.”

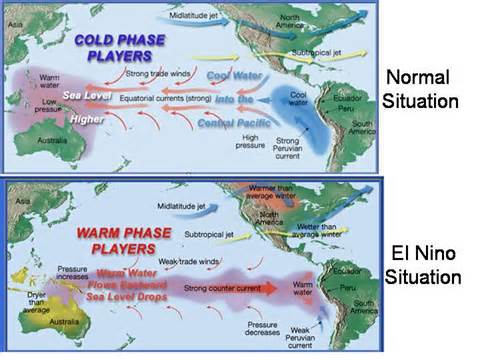

Every time El Niño strikes, food production suffers. During the climate-related phenomenon, intense heat dries up farmlands, reservoirs and waterways all over the country. Water is needed to grow crops and without it, the crops wither and ultimately die. Those who survived may not give the best optimum level, thus the production is very low.

In some parts of the country, the bad boy weather has whipped various crops of farmers. In Pagadian City, for instance, the council declared the city under a state of calamity as drought has affected more than a thousand farmers. In Cebu, the town of Carmen has also been declared under the same situation as farmers and residents suffer scarcity of water.

Adang said he is just “little bit worried” because the center has an upland farming technology that can substantially defy the onslaught of El Niño. He is referring to the Sloping Agricultural Land Technology (SALT), which has been observed to produce crops despite the long drought.

During the El Niño that happened in 1983, the cost and return analysis of the SALT demonstration plot still managed to give a monthly net income of P436.90. “The income may not be that huge but just remember that the study happened thirty-six years ago,” he reminded. “And it’s already net income and not gross income.”

The previous recorded figure, in 1982, was P597.85 per month. Reported studies showed that most upland farmers in the country during that time get a measly income of only P300 per month.

In 1990, when another drought hit Mindanao, the SALT system had a monthly net income of P1,277.31. This was only 54.34 lower than the previous reported monthly net income of P1,331.74 in 1989.

SALT introduces a scheme whereby denuded uplands can be made productive for farmers using locally available materials. Planting leguminous trees and shrubs closely as “belts,” this technology conserves soil and water, making the uplands more favorable for the sustained production of many annual and perennial agricultural crops.

“I think the reason why our SALT farm still yields crops was due to the hedgerows planted along the contours of the farm,” said Adang, who used to work with some upland farmers in other parts of Asia.

Among those that are used for hedgerows are locally-grown “ipil-ipil” (Leucaena leucocephala) and “kakawate” (Gliricidia sepium). Introduced species like Flemingia macrophylla, Indigofera anil, and Desmodium rensonii can also be used. “They all fix nitrogen from the air,” Adang said. “As such, they help fertilize the soil with the droppings of their leaves.”

The hedgerows are cut down when they are one meter tall or when they begin to shade crops. “The cut branches with leaves are piled at the base of the crops to serve as fertilizer,” Adang said. “They also serve as mulching materials so that the moisture can be retained in the soil.”

That’s partly one of the main secrets of the SALT scheme. A study, which started in 1991 and ended in 1994, was done at the center between traditional farming and SALT farming. It was aimed in measuring the moisture availability of soil at a six-inch depth.

“Our study showed that each of our SALT components tends to have more available moisture than the non-SALT farming system at the six-inch depth,” Adang claimed, adding that the trees within a cropping system do not necessarily compete for moisture. “In fact, they may benefit one another in the long run,” he points out.

In the SALT system, various crops are planted. “Doing so means a farmer can have a harvest every now and then,” Adang said. “Planting several crops also minimize pest infestation and help control diseases among crops.”

Permanent crops – like cacao, coffee, banana, and fruit trees – can be planted at the same time when nitrogen fixing tree and shrub species (NFTSS) are planted. Permanent crops are planted on every third strip. On the first and second strips, short-term and medium-term crops are grown.

“The crops grown in first and second strips become the source of income for the farmers and in some instances foods for the family. It may take sometimes for the permanent crops to bear fruits. “Short crops should be planted away from tall ones to avoid shading,” reminded Adang.

Crop rotation is also practiced in the SALT farm. “A good way of crop rotation is to plant grains (corn, upland rice, and sorghum), tubers (sweet potato, cassava, and “gabi”), and other crops (vegetables, legumes, and peas) on strips where legumes were previously planted and vice versa,” Adang suggested. “This practice will help maintain the fertility and good condition of the soil.”

The SALT scheme is also a good way of controlling soil erosion. Generally, after a long drought, a farm is barren and without cover. So, when a big rain comes, all the topsoil is washed out.

In a study done by MBRLC, it was found that SALT is very effective in controlling soil erosion because of the thickly planted NFTSS. “Where the non-SALT system yields a total of almost 1,200 tons of erosion over the six-year study, the SALT farms only yields a total of 20 tons,” Adang said.

Computing the data, the study showed that the annual rate of soil loss for SALT system is 3.4 tons per hectare per year. “This is much less than the non-SALT system, which is 194.3 tons per hectare per year,” said Adang.

Both the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and the Department of Agriculture (DA) are recommending the adoption of SALT as a way to cushion the impacts of the looming El Niño.

“SALT is an agroforestry technology which combines agricultural and forestry crops in a single land, at a percentage ratio of 75:25,” points out the book, El Niño Southern Oscillation: Mitigating Measures, published jointly by DOST and DA. “This technology can help reduce soil erosion four times, increase the yield crop five times, and improve income six times.” (To be continued)