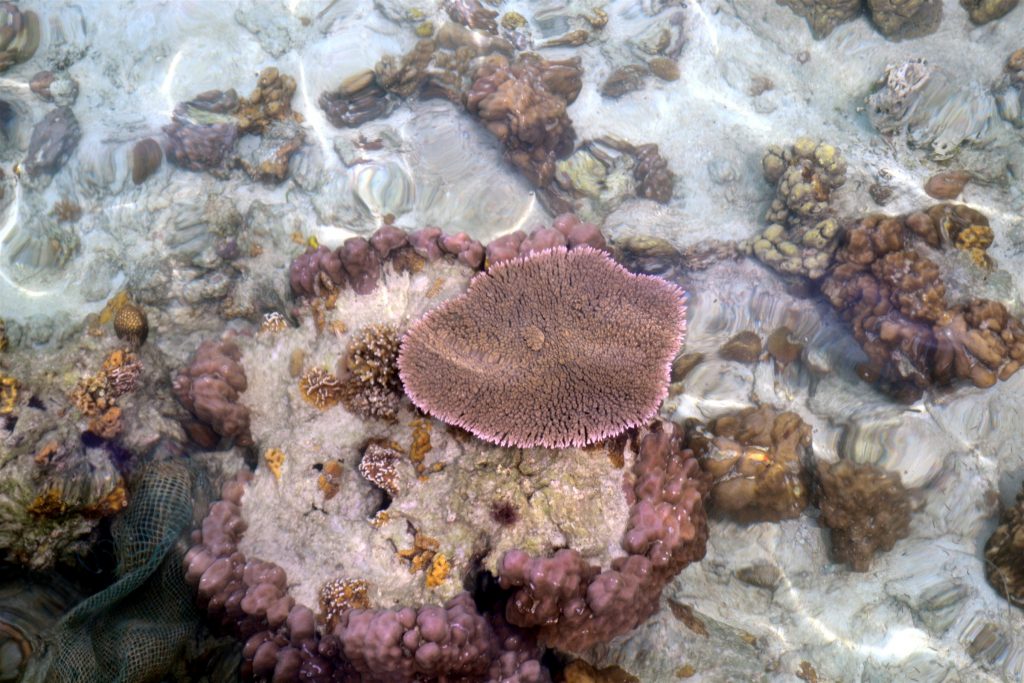

In July last year, Romina Lim posted in her Facebook account some photos of Tubipora and Heliopora corals that were “exported” from the Philippines in a gift shop in Long Beach, Washington.

“Labels say these were ‘rare’ and exported all the way from the Philippines. These corals were extracted from our reefs then sold in the US for less than P2,000 [$37.50]),” wrote Lim in her social media account.

“Do not support this trade,” Lim urged in her post, which caught the attention of an online reporter for Interaksyon. “Philippine law specifically prohibits the collection and exportation of all corals (unless, of course, for scientific and educational purposes). Corals are worth much more alive in coral reefs than dead displayed at your houses.”

According to her, she reported the incident to various Philippine agencies, but so far only the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), a line agency of the Department of Agriculture, responded.

“Heads will roll if perpetrators are from BFAR side. I will conduct investigation ASAP. The law is harsh, swift, and painful. And more harsh, more swift, more painful if perpetrators are from within the implementors of the law,” said BFAR Director Eduardo Gongona.

About 100 scientists have proclaimed the Philippines as the world’s “center of marine biodiversity” because of its immense number of species and marine and coastal resources. It has 27,000 square kilometers of coral reef area within a 15- to 30-meter depth, one of the largest in the world. Two-thirds of these are in Palawan and the Sulu Archipelago. There are about 400 species of reef-forming corals in the country, which can be compared with those found in Great Barrier Reef of Australia.

“Almost 55% of the fish consumed by Filipinos depends on coral reefs; 10-15% of the total marine fisheries production comes from the coral reefs,” reports Dr. Miguel D. Fortes, a professor at the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines.

Fish, along with rice, is the staple food of Filipinos. Every year, a Filipino consumes almost 30 kilograms of seafood, thus making the country one of the world’s biggest fish consumers.

One square kilometer of healthy coral reef can generate about US$50,000 annually from fishing and tourism. “As a whole, Philippine coral reefs contribute at least US$1.4 billion annually to the economy,” states the report, From Ridge to Reef: Sustaining Nature for Life.

But despite their contributions, coral reefs are destroyed at alarming rate. Nowhere else in the world are coral reefs abused as much as the reefs in the Philippines. In 2002, some of the top leading marine scientists ranked the country as the number one (according to the degree of threat) among the world’s top ten coral reef hotspots. The identified hotspots contain just 24% of the world’s coral reefs, or 0.017% of the oceans.

The World Atlas of Coral Reefs, compiled by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), reported that 97% of reefs in the Philippines are under threat from destructive fishing techniques, including cyanide poisoning, over-fishing, or from deforestation and urbanization that result in harmful sediment spilling into the sea.

Rapid population growth and the increasing human pressure on coastal resources have also resulted in the massive degradation of the coral reefs. “If asked what the major problem of coral reefs is, my reply would be, ‘The pressure of human populations,’” said marine scientist Dr. Edgardo D. Gomez, one of the country’s experts on coral reefs.

Robert Ginsburg, a specialist on coral reefs working with the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami, said human beings have a lot to do with the rapid destruction of reefs. “In areas where people are using the reefs or where there is a large population, there are significant declines in coral reefs,” he pointed out.

As a result, fish catch in the open seas dwindles. “Fish catches have fallen well below the sustainable levels of healthy reefs,” said Dr. Alan T. White, who conducted various studies on coral reefs in the Philippines. “The economic losses to the coastal fishing population are considerable. Various programs have and are trying to counter coral reef decline by establishing sustainable management regimes. The economic benefits of such programs appear to exceed their investment costs.”

Aside from human activities, natural causes of destruction among coral reefs also occur. These include extremely low tide, high temperature of surface water, predation, and the mechanical action of currents and waves.

In recent years, corals are also exhibiting a new kind degradation: massive bleaching. John C. Ryan, in a feature written for Worldwatch Institute, explained: “When subjected to extreme stress, they jettison the colorful algae they live in symbiosis with, exposing the white skeleton of dead coral beneath a single layer of clear living tissue. If the stress persists, the coral dies.”

The government is doing its best to save the country’s remaining coral reefs by passing several laws. Fisheries Administrative Order 163, Series of 1986, prohibits the operation of “muro ami” and “kayaks” – both destructive fishing practices that destroy coral reefs – in all Philippine waters.

Presidential Decree 1219 prohibits person or corporation to “gather, possess, sell or export ordinary precious and semi-precious corals, whether raw or in processed form, except for scientific or research purposes.”

Violation of the said law would result in imprisonment from six months to two years and a fine from P2,000 to P20,000. However, this law was amended through Republic Act 10654, or the Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998. It states that no person or corporation shall “gather, possess, commercially transport, sell or export ordinary, semi-precious and precious corals, whether raw or in processed form, except for scientific or research purposes.

Once it is violated, there would be a corresponding “administrative fine equivalent to eight times the value of the corals gathered, possessed, commercially transported, sold, or exported, or the amount of P500,000 to P10 million, whichever is higher, and forfeiture of the subject corals.”

There are laws but imposing them is another story. “Stricter laws on environmental crimes must be imposed because exploiting marine resources is not a simple offense,” says Dr. Theresa Mundita Lim, executive director of ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity. “It may jeopardize the livelihood source of the millions of people who depend on these resources.”

Loren Legarda, an environment champion in the Senate, urged the local and national government to unite in addressing the problem of reef deterioration. “It is imperative that local government units should take an active role in promoting environmentally sound practices especially those near the sea,” she said. “The Philippine Coast Guard and other law enforcement arm of the government should redouble their efforts to stop marine activities that harm the ecosystem.”

But the government cannot do it alone; help from individuals are also needed to save the coral reefs from total annihilation.

“We are the stewards of our nation’s resources,” said Rafael D. Guerrero III, former executive director of the Philippine Council for Aquatic and Marine Research and Development, “We should take care of our national heritage so that future generations can enjoy them. Let’s do our best to save our coral reefs. Our children’s children will thank us for the effort.” (To be concluded)