“Measles is incredibly resilient and our success is fragile. If we drop our guard, this disease will regain a foothold and spread like wildfire once again. We must stay vigilant.” — Dr. Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Chairman of the American Red Cross, 2009

***

Eighteen-month-old Jessie was an active, playful toddler. Then, one day, he was struck down with a high fever, severe coughing, diarrhea, vomiting and a red rash on his face and chest.

When Jessie started gasping for breath on the sixth day of his illness, his parents rushed him to a hospital. The doctor diagnosed pneumonia, a complication of measles. Although he was given intravenous fluids and antibiotics, his condition worsened. Two days after admission, Jessie died.

Sarah, the boy’s mother, later told doctors she didn’t realize that measles was life-threatening. She hadn’t had Jessie vaccinated against the disease even though she lived just over a kilometer away from a health center. “If only I had known,” she said.

With vaccine available for measles, the acute bacterial respiratory infection should have been part of history already – but such is not the case.

In fact, it has returned as a major public health threat. In 2011, for instance, 158,000 people from around the world – mostly children under the age of five – died of measles. That’s 18 deaths every hour or 430 deaths every day. “More than 95% of measles deaths occur in low-income countries with weak health infrastructures,” the World Health Organization (WHO) reported.

Most of those hit by measles are developing countries, including the Philippines. In 2014, measles was a real battle in the country, with the final measles tally at 58,010 cases, according to the WHO. The figure included 110 people, mostly children, who lost their lives to the contagious virus.

The battle continues even today. A surveillance report from the Department of Health (DOH) showed that from January to March 2017 there was only one reported measles case in Davao Region but it surged to 167 cases (with five deaths) the following year on same time period.

The Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao trailed with 157 cases (but no reported casualty) from one case in 2017. Other regions with increasing number of measles cases were Region 9 (114 cases from 6 cases), Region 12 (87 cases with one death from no reported case the previous year), National Capital Region (86 cases and 5 deaths from two cases in 2017), and Region 10 (59 cases with one death from one case).

According to the surveillance report, the top provinces with confirmed cases from 2015 to 2017 were Davao del Sur (107 cases), Metro Manila (87), Zamboanga del sur (76), and Maguindanao (61).

“Areas with declared epidemics were: Davao City, Zamboanga City, Isabela City in Basilan, Alicia in Zamboanga Sibugay, Taguig City in Metro Manila, and some municipalities in Antique,” the surveillance report pointed out

From January to March 2018, the health department’s Public Health Surveillance Division also tried to figure out if those confirmed measles were vaccinated against the disease. Majority (80%) were unvaccinated.

“Top reasons for non-vaccination of measles-containing vaccine among confirmed cases were: not eligible for vaccination (28%), mother was busy (20%), and child was sick (16%),” the report stated.

Other reasons cited were schedule forgotten, difficult access to health services, and fear of side effects. There were also children not vaccinated because it was against their belief, moved residence, war conflict, refusal of parents, lack of knowledge, child was abandoned, and history of travel.

Some people believe that the recent spike of measles cases in the country was due to “the low trust in the government’s mass immunization program” as a result of the controversial anti-dengue vaccine which, according to the Public Attorney’s Office (PAO), has resulted in the deaths of several children who were vaccinated.

“Since I assumed office in November 2017, I found myself faced with the Dengvaxia crisis,” Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, said in a television interview in January 31. “In attempt to collaboratively resolve this issue, we also reached out to various government agencies, including the Public Attorney’s Office. Unfortunately, my fellow public servants… refuse to cooperate. As a consequence, we saw a decline in vaccine confidence and a rise in cases of measles and other vaccine preventable diseases.”

PAO’s Atty. Persida Acosta, in a television report in February 6, responded: “Iyong kakulangan nila sinisisi nila sa PAO eh sila itong hindi nagbakuna ng measles vaccine sa mas nakararaming Pilipino. Inatupag nila Dengvaxia. Ano ba ang binabakunahan ng measles vaccine, ‘di ba one year old? Bakit ‘di nila binabakunahan? Bakit ‘di sila nangumbinsi?”

As a result of imbroglio and lack of immunization of Filipino children, the health department feared that about 2.4 Filipino children are at risk of getting infected with measles. “We are impending that we will have another outbreak for this year,” Dr. Ruby Constantino, director of the DOH Disease Prevention and Control Bureau told CNN Philippines in a television interview.

Measles has often been described “the simplest of all infectious diseases.” It is probably the most “visible” infection due to a consistent clinical picture and the fact that virtually everyone contracted it before vaccination was introduced in the early 1960s.

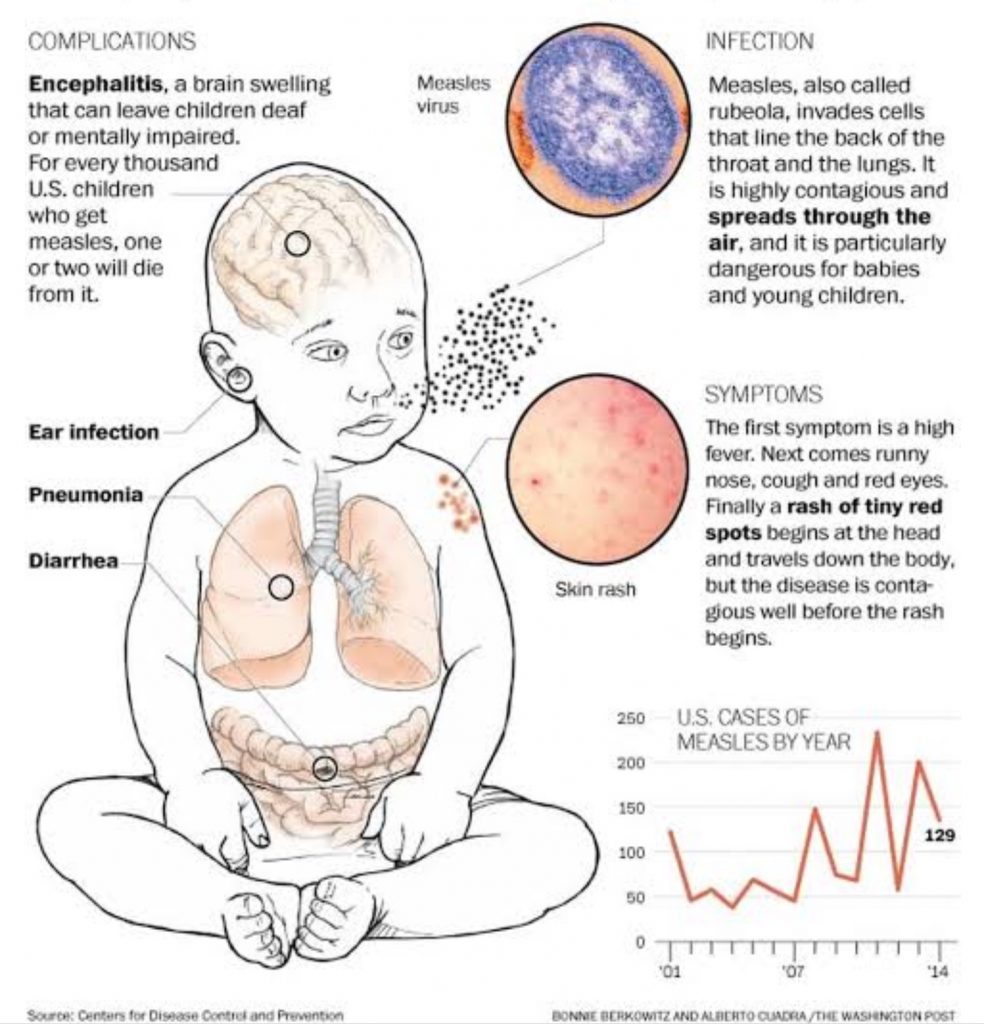

Also called rubeola, measles is a highly contagious viral disease. It usually affects children but can occur at any age in susceptible persons. A person who has been infected with measles become immune for life.

The measles virus is not the same virus that causes German measles, or rubella. “The virus is spread by droplets from the mouth or throat secretions,” explained Dr. Donald M. Vickery and Dr. James F. Fries, authors of Take Care of Yourself.

The measles virus, which remain suspended in their air for several hours, can only be killed by sunlight. It is very active during the cold months, particularly December to January.

Measles – locally known as “tigdas” or “tipdas” – is a very contagious illness caused by a virus in the paramyxovirus family (which also caused mumps, German measles and chicken pox). “The measles virus normally grows in the cells that line the back of the throat and lungs,” the WHO said. “Measles is a human disease and is not known to occur in animals.

Measles is easily spread by contact with droplets from the nose, mouth, or throat of an infected person. Sneezing and coughing can put contaminated droplets into the air. “The virus remains active and contagious in the air or on infected surfaces for up to two hours,” the WHO said.

Those who have had an active measles infection or who have been vaccinated against the measles have immunity to the disease. Before widespread vaccination, measles was so common during childhood that most people became sick with the disease by age 20.

Due to a boost in global efforts to vaccinate people against measles, total cases declined. But in 2010, cases of measles increased again, driven largely by outbreaks, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The outbreaks were mainly linked to low vaccination coverage of the population, in some cases due to little access to health services. There are also parents who do not let their children get vaccinated because of unfounded fears that the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella, can cause autism. Large studies of thousands of children have found no connection between this vaccine and autism.

“Not vaccinating children can lead to outbreaks of a measles, mumps, and rubella – all of which are potentially serious diseases of childhood,” reminded Dr. Neil K. Kaneshiro, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Health Assistant Secretary Eric Tayag said that a person infected with measles can infect up to 12-13 more people. So, how will you know that a person has measles?

“The first sign of measles is usually a high fever, which begins about 10 to 12 days after exposure to the virus, and lasts four to seven days,” the WHO informed. “A runny nose, a cough, red and watery eyes, and small white spots inside the cheeks can develop in the initial stage.

“After several days, a rash erupts, usually on the face and upper neck. Over about three days, the rash spreads, eventually reaching the hands and feet. The rash lasts for five to six days, and then fades. On average, the rash occurs 14 days after exposure to the virus (within a range of seven to 18 days).”

Most measles-related deaths are caused by complications associated with the disease. Complications are more common in children under the age of five, or adults over the age of 20. The most serious complications include blindness, encephalitis (an infection that causes brain swelling), severe diarrhea and related dehydration, ear infections, or severe respiratory infections such as pneumonia.

“As high as 10% of measles cases result in death among populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate health care,” the WHO said. “Women infected while pregnant are also at risk of severe complications and the pregnancy may end in miscarriage or preterm delivery.”

One good thing: People who recover from measles are immune for the rest of their lives.

Among those who are at risk of being infected with measles are unvaccinated young children; they are at highest risk of measles and its complications, including death. Unvaccinated pregnant women are also at risk. Any non-immune person (who has not been vaccinated or was vaccinated but did not develop immunity) can become infected.

Until now, no specific antiviral treatment exists for measles virus. But it can be prevented, according to the Philippine Red Cross (PRC). It urges mothers to have their children immunized with measles vaccine at 9 months old.

“In case of measles outbreak, measles vaccine can be given again to infants (6 months old), children and adults by health workers,” PRC says, adding that vitamin A supplementation may be given during routine measles vaccination.

Severe complications from measles can be avoided though supportive care that ensures good nutrition, adequate fluid intake and treatment of dehydration with WHO-recommended oral rehydration solution. This solution replaces fluids and other essential elements that are lost through diarrhea or vomiting. Antibiotics are prescribed to treat eye and ear infections, and pneumonia.

Even in countries with good health services, measles can be very serious, particularly in young children, according to Dr. Peter Strebel from the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals at the WHO.

“Measles still causes an estimated 197, 000 deaths each year around the world, the majority of them children under the age of five. Parents and doctors need to be reminded that measles is a highly contagious disease,” he said.