With two deaths out from the 249 dengue cases from January to June 2019 this year, the local government unit (LGU) officials of the Island Garden City of Samal has placed the city “under the state of calamity.”

“Due to the increased number of incidents of dengue fever, the LGU officials deemed it necessary to declare the said outbreak and ordered involved agencies to release funds and adopt quick response to counter the dengue cases outbreak,” the Samal Island Information posted in its social media account.

“The number of dengue cases dramatically increased up to 730% higher compared to the same period last year,” said in part the minutes of the second regular session of the Sangguniang Panglungsod.

But it’s not only in Samal that spike of dengue cases is

going on. Other parts of the country are also experiencing the same

situation. In fact, a National Dengue Alert has been issued by Dr.

Francisco Duque III of the Department of Health (DOH) due to “rapidly”

increasing number of cases reported in several regions.

From January 1 up to June 29 this year, about 106,630 dengue cases have been

recorded based from the data compiled by the health department.

In Davao City, the DOH regional office reported 1,039 dengue cases (with one death) from January 1 to May 16, 2019. In the same period, one death each were also recorded in Davao del Sur, Davao Oriental, and Davao Occidental.

In Samal, the declaration of the state of calamity was based on the CDRRMC (City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council) Resolution No. 6, Series of 2019. The minutes quoted Section 2 of Republic Act No. 10121 which said “the State recognizes the role of the LGU in strengthening the capacity of communities in mitigating and preparing for, responding to, and receiving from the impacts of disasters including climate change.”

In a study entitled Human Health and Climate Change, Dr. Paul Epstein said that a warming climate, compounded by widespread ecological changes, may be “stimulating wide-scale changes in disease patterns.”

The Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) thinks so, too. “Climatic conditions strongly affect water-borne diseases and diseases transmitted through insects, snails or other cold-blooded animals,” it says.

The dengue fever, most common mosquito-borne viral disease of human beings, is a case in point. Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), the more lethal form, was first recognized during the 1950s. The Philippines reported a DHF epidemic in 1953-45, according to the Philippine Journal of Pediatrics.

Before 1970, only nine countries had experienced dengue and DHF epidemics. Today, the disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries. Before 1970, only nine countries had experienced severe dengue epidemics. The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries, with Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific regions as among the most seriously affected.

According to WHO, there may be 50–100 million dengue infections worldwide every year. With climate change going on, more infections are now reported in various parts of the world.

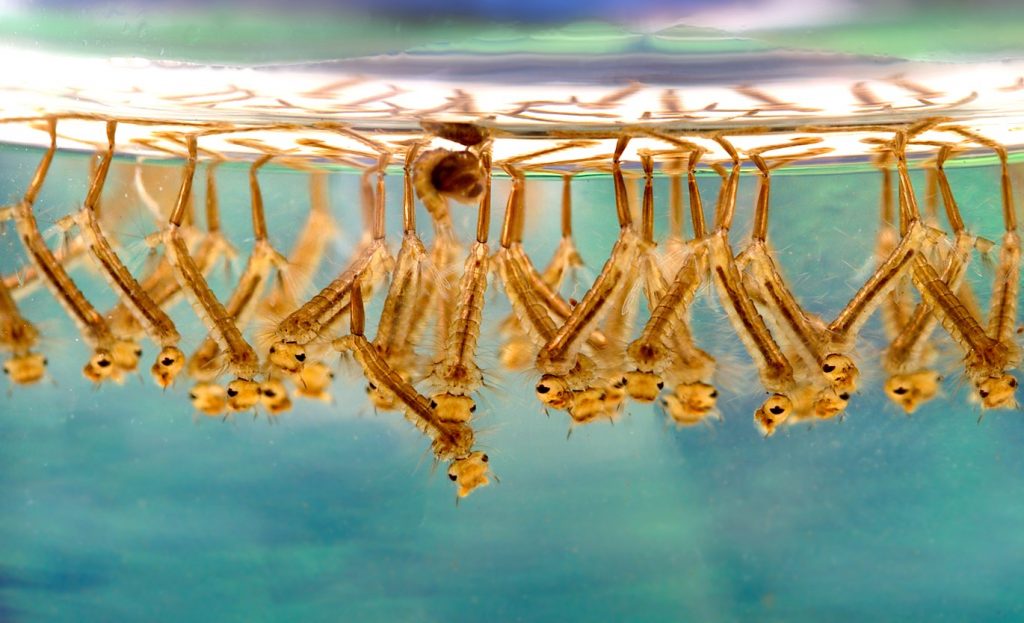

Dengue is found in tropical and sub-tropical climates worldwide, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas. “Dengue is the world’s most important viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes,” declares Dr. Duane Gubler, health administrator of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The mosquitoes become infected when they feed on someone who has the virus.”

When the female mosquito gorges the blood of an infected human, the virus enters the insect’s salivary gland, where it incubates for eight to ten days. After that, the mosquito can pass the virus on to the next person it bites.

The dengue virus does not spread directly from person to person, health experts claim. However, it is the infected humans who are the main carriers and multipliers of the virus. This is the reason why if there is someone in your neighborhood who has dengue, it is most likely more people will become infected. “Patients who are already infected with the dengue virus can transmit the infection via Aedes mosquitoes after their first symptoms appear,” the WHO says.

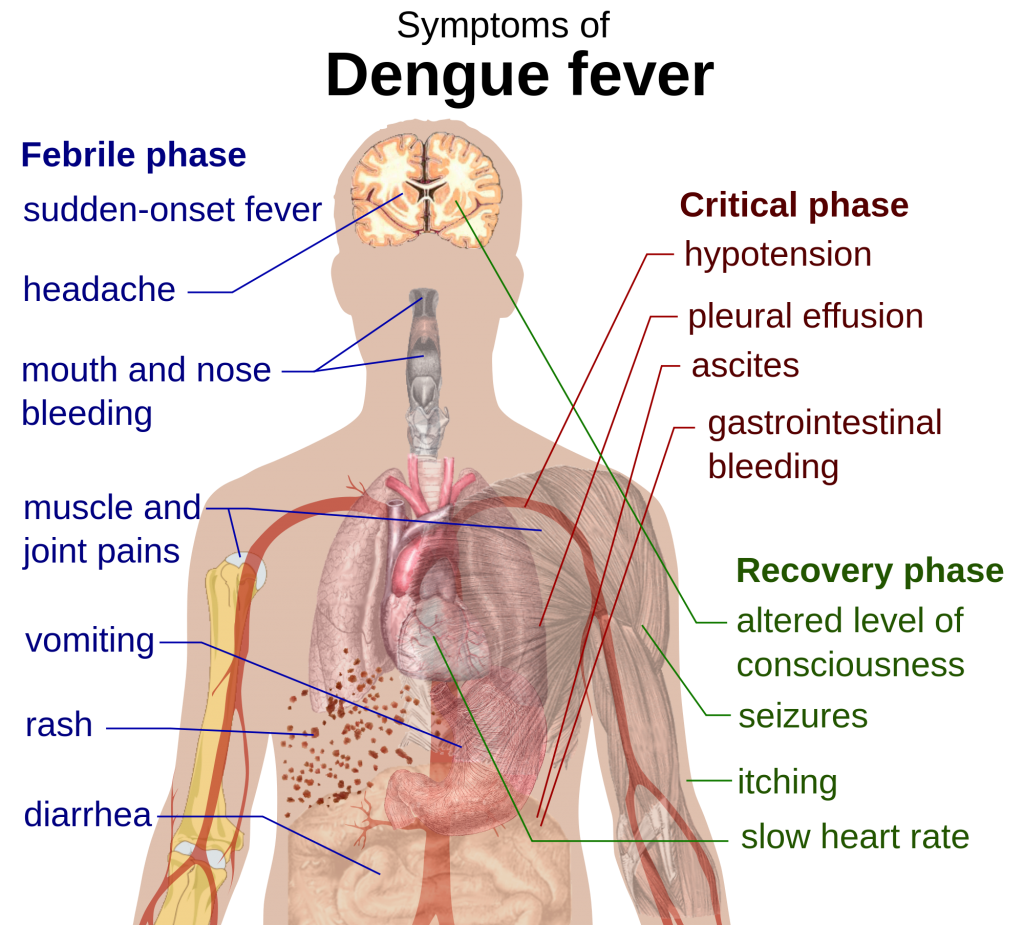

Dr. Richard T. Mata, a dengue consultant with the WHO Philippines, said that dengue is marked by an onset of sudden high fever, pain behind the eyes, and pain in muscles and joints.

“A patient who is persistently weak even when the fever has subsided is a big sign of dengue,” Dr. Mata says, adding that not all dengue cases have rashes. “Don’t wait for rashes to think of dengue.”

This is the febrile phase of dengue, which usually last 2-7 days, according to the website of the Department of Health (DOH). In case the results of the blood platelet are not low, there is still a need to repeat daily “especially if the patient is still weak.” Dr. Mata says platelet becomes low by third day of fever – 72 hours from start of fever.

As such, it is advisable to bring those with fever on the second or third day of fever to a hospital. If you bring the patient on the fourth day of fever, it is already late. “If diagnosed as dengue, the doctor will advise either home care or for admission,” Dr. Mata says.

It happened to six-year-old Lenny, who was struck with fever one night after two days of rain. But there was something different; she appeared flushed. She was irritable and had poor appetite although she never complained about food. Sarah, the mother, observed that her daughter’s flushed skin had some white areas but she just ignored it.

Sarah thought the fever was just ordinary so she did not bring her daughter to her doctor and instead gave her paracetamol, which she believed would help subside the fever. The fever vanished one day only to return the following day. On the fourth day of on-and-off fever, Lenny experienced what most doctors called as “shock.”

“Lenny was breathing rapidly,” Sarah recalled. “She was restless and her pulse was beating fast. Her skin was cold and clammy and she felt drowsy all the time. She was vomiting and bloods were oozing from her mouth. Before, she completely lost consciousness.”

Sarah brought her daughter to the nearest hospital, some thirty minutes away from home. One of the doctors tried pull Lenny out of shock by replacing the fluids and blood she lost but it was all in vain. The doctor failed to save her.

The critical phase of dengue happens when the patient can either improve or deteriorate. Defervescence, the period in which the body temperature (fever) drops to almost normal (between 37.5⁰C to 38⁰C), occurs during this phase.

“Those who will improve after defervescence will be categorized as dengue without warning signs, while those who will deteriorate will manifest warning signs and will be categorized as dengue with warning signs or some may progress to severe dengue,” the DOH website states.

Dengue “seldom causes death,” WHO points out but it becomes deadly when it develops into severe form called dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF). “Warning signs occur 3-7 days after the first symptoms in conjunction with a decrease in temperature and include: severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, rapid breathing, bleeding gums, fatigue, restlessness and blood in vomit,” the WHO says.

Dr. Lulu Bravo, a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Medicine, said that in DHF, cells release chemicals that trigger leakage of plasma from blood vessels. “Fluids accumulate in body cavities, causing profound shock. Death often results from bleeding in the brain, intestines or other organs,” she told EDGE Davao in an e-mail interview.

Dengue, according to Dr. Mata, is one of the most misunderstood diseases in this planet. Most people are terrified of dengue because when the blood platelets decrease, it causes severe bleeding and ultimately death. This thinking, he says, is very wrong.

He says that what really kills a person with dengue is not due to low platelet counts but dehydration. It occurs when a person loses more fluid and his body doesn’t have enough waterand other fluids to carry out its normal functions.

Dehydration causes intestinal ulcer that causes bleeding. “And because the platelets are low, the bleeding becomes severe. But if there was no dehydration, there will be no ulcer andthus no bleeding – even if the platelets are low,” he explains. “So, it still boils down to dehydration.”

Dehydration also causes kidney failure, which result from the decrease in urine output. “This causes the water to be retained in the lungs thereby creating congestion that can kill the patients,” he says.

Many people believe congestion is caused by over hydration. “But the truth is, it is caused by kidney failure due to dehydration,” he says. “That’s ironic, right?”

According to Dr. Mata, Thailand and Sri Lanka has zero casualties when it comes to dengue (compared to 1,000 deaths annually in the Philippines). “These countries never said they got a drug from herbs or something; they said its about correct fluid management,” he says.

Research in the aforementioned countries are focused more on fluid management. In comparison, most Filipino researchers “focused on herbs which are actually or are already being used by many but still the deaths are high,” Dr. Mata laments.

“In severe dengue, the blood vessels leak of fluids until the blood pressure drops,” says Dr. Mata, a pediatrician who has a clinic in Panabo City in Davao del Norte. “Dehydration is the killer; low platelet is only secondary.”

Thus, he advises to hydrate the patient with oral rehydrating solution or other fluids like coconut water, fruit juices and water. “Monitor urine output and record the amount and the time.

Once the patient is no longer urinating regularly, it is already a red flag. “A clear urine with good amount and less than four to six hours in intervals is a good sign of hydration,” he explains.

Medical science says dengue is caused by four distinct virus serotypes (varieties recognized as distinct by the immune system). “Some can be managed by oral hydration, some need intravenous hydration,” Dr. Mata points out. “Let the doctor decide during early consultation.”

An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure, so goes a saying. The best way to prevent dengue fever is by cleaning up mosquito breeding sites in the area. Without the carriers, there will be no dengue.