If it was tuberculosis (TB) in the past, then it’s hepatitis B today. Both are serious public health problems and they have one thing in common: discrimination.

In the olden times, people with TB were isolated from the rest of the community. As the bacteria can be transmitted through the air, people abhorred from talking or getting near with them.

The same thing happens today to people with hepatitis B. Friends try not to associate with those infected with the virus. There are even family members who separate kitchen utensils for those with hepatitis B fearing they would be infected.

The fear is understandable but people with hepatitis B shouldn’t be discriminated. “Many people believe hepatitis B can be transmitted to casual contact,” said Dr. Janus Ong, a transplant hepatologist. “They do not know that the virus can be unknowingly transmitted through contaminated blood products including during transfusions, contaminated medical devices and from infected mothers to infants during children.”

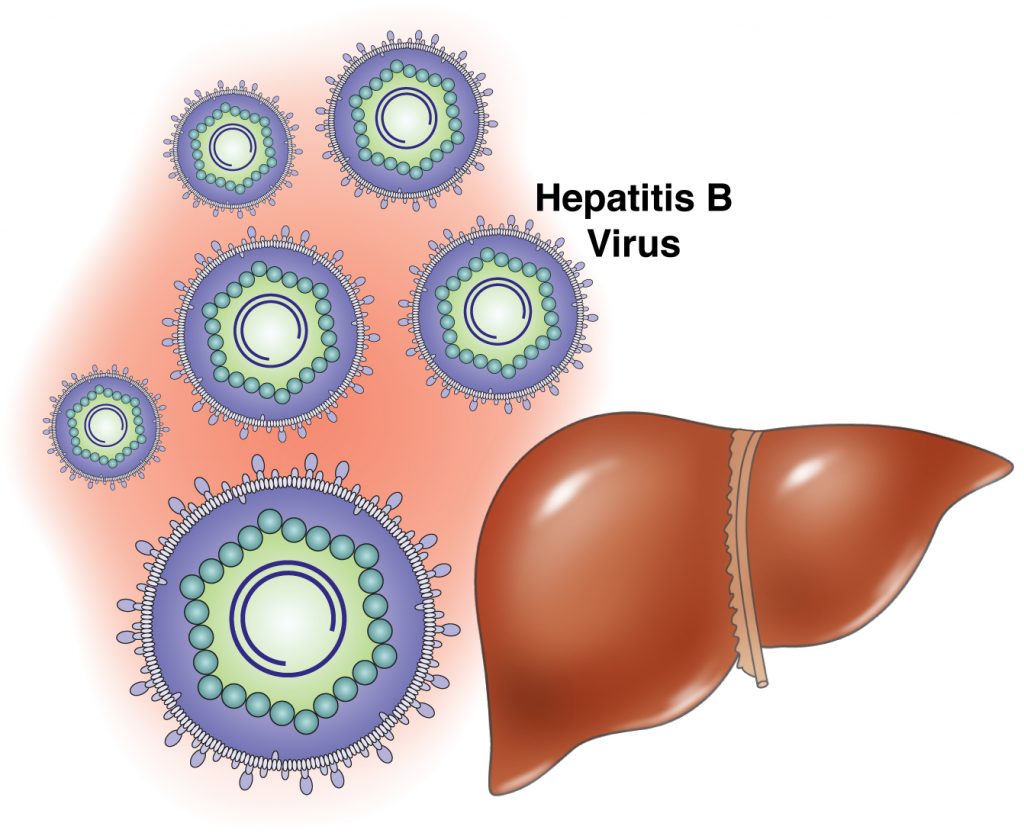

But that’s going ahead of the story. Hepatitis, the inflammation of the liver, has several causes, including heavy alcohol intake, some toxins and drugs, other systemic diseases, and some infections. Of the infectious causes of hepatitis, viral infections, particularly hepatitis A, B, and C, are most common.

The Merck Manual of Medical Information says hepatitis can either be acute (short-lived) or chronic (lasting at least 6 months). In the Philippines and worldwide, most people with chronic hepatitis B acquired the infection at birth or during early childhood.

Based on the 2016 estimates of the World Health Organization (WHO), around 8.5 million Filipinos are chronically infected with the hepatitis B. Prevalence of the contagious infection is very high at 16.7%. This means one in 7 Filipino are infected by the virus, which is 50 to 100 times more infectious than the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). A study conducted in 2003 showed the prevalence was highest among the 20-49 age group, which comprise the country’s workforce.

Just like HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV) can be passed on to another person through the body fluids, such as semen, vaginal fluids and blood, according to Hepatology Society of the Philippines (HSP).

A person may acquire the infection through the following: birth (spread from a hepatitis B positive mother to her baby), sex with an infected partner, direct contact with the blood or open wounds of an infected person, and exposure to blood from needlesticks or other sharp instruments.

In addition, a person may get it through sharing needles, syringes, and other drug-injection equipment with an infected person. Razors, nail clippers/manicure or pedicure paraphernalia or toothbrushes may also transmit the disease if they are used by an infected individual.

But the virus is not spread through food and water. As such, HBV is “not spread by sharing utensils, sharing drinks, breastfeeding, hugging, kissing, holding hands, coughing, or sneezing,” HSP assures. Unlike HIV, however, HBV can survive outside the body and can cause infection for at least 7 days.

Not everyone exposed to hepatitis B develop symptoms. “Although majority of adults develop symptoms from acute hepatitis B infection, many young children do not,” HSP says. “Adults and children over the age of 5 years are more likely to have symptoms. Seventy percent of adults will have symptoms from an acute hepatitis B infection.”

Symptoms of acute hepatitis B include: fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, clay-colored stool, joint pains, and jaundice (yellow color in the skin or the eyes). “Symptoms can appear 90 days after exposure, but they can also manifest between 6 weeks and 6 months after exposure,” HSP informs.

Generally, people with acute hepatitis B have symptoms for a few weeks, although some may fell ill for as long as 6 months. But there are people who may be infected with HBV and yet they look healthy and have no symptoms; still they can spread the virus.

Most people with chronic hepatitis B may not experience symptoms and may feel healthy for many years. “About 15% to 25% of people with chronic hepatitis B develop complications in the liver, such as cirrhosis or liver cancer,” HSP points out. “In the early stages of liver cirrhosis and live cancer, patients may remain to have no symptoms. However, tests for liver function or liver ultrasound might begin to show some abnormalities.”

Chronic hepatitis B shouldn’t be ignored as it can result in liver damage, liver failure, liver cancer, or even death. In the Philippines, liver cancer is the third leading cancer, affecting over 7,000 new Filipinos every year. “Liver cancer carries a poor prognosis, making it the second leading cause of cancer death locally,” HSP claims.

But the good thing is: both acute and chronic hepatitis Bs can be treated. In acute hepatitis B, the main treatment is mostly supportive, that is, in the form of rest, adequate nutrition and adequate hydration.

For chronic hepatitis B, there are now several drugs available. “The choice of antiviral drug may depend on the patient,” HSP says. “However, not all patients which chronic hepatitis B need antiviral drugs. Patients should be evaluated by health professionals experienced in the management of hepatitis B.”

Another good news: hepatitis B can be prevented through a vaccine. “The vaccine is given as a series of 3-4 shots over a period of 6 months,” HSP says. “It stimulates the body’s immune system to produce the antibody that protects against hepatitis B.”

Studies have shown that once the person has been given the vaccination series, he or she is “greater than 90% protected” compared to those immunized before being exposed to hepatitis B.

The safety of the hepatitis B vaccine has been evaluated by many leading health authorities including the United Nations health agency and the United States Institute of Medicine. “The hepatitis B vaccine is safe,” HSP assures. “Pain at the injection site is the most common side effect reported.”

But despite the availability of hepatitis B vaccine and treatments, people with hepatitis B are still discriminated.

“Every week, I see so many new patients with hepatitis B and liver cancer, it’s frightening,” Dr. Ong deplores. “But here is still so much stigma and discrimination that no one wants to step up as a champion.