“The jury is still out on what overall impact global warming would have on food production. Predictions do not need to be 100% accurate. They need merely to be sufficient for us to change our attitudes; they need merely to illustrate the potential cost of inaction.” – Dr. Peter Usher, of the United Nations Environment Program

***

The world, with surging population, is not only getting smaller in terms of land area for food production; it is also getting hotter!

Since 1880, respected scientists say the worldwide average temperature has increased by about 0.9⁰F. This, they point out, is within the normal fluctuations range, meaning it could be a short-term change that will return to normal in the near future.

Sadly, instead of returning to normal, the temperature is getting warmer each year. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a United Nations-sponsored body made up of more than 1,500 leading scientists from all over the globe, projected an increase of the planet’s average surface temperature to be between 2.5⁰F and 10.4⁰F between 1990 and 2100.

The escalation of the world’s temperature is the result of the increasing concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere. GHGs include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Scientists call this phenomenon as “greenhouse effect.” In an article published in Reader’s Digest, Robert James Bidinotto explained in these words: “When sunlight warms the earth, certain gases in the lower atmosphere, acting like a glass in a greenhouse, trap some of the heat as it radiates back into space. These greenhouse gases warm our planet, making life possible.

“If they were more abundant, greenhouse gases might trap too much heat,” Bidinotto continued. “But if greenhouse gases were less plentiful or entirely absent, temperatures on Earth would average below freezing.”

Because concentrations of GHGs have been steadily increasing in recent years around the globe, the world’s average temperature has completely changed.

Six years ago, the government-initiated Climate Change Commission (CCC) listed the Philippines as among the top ten countries most vulnerable to the impacts of this global phenomenon.

Most areas in the Philippines will experience reduced rainfall from March to May, making the dry season drier, according to the 2018 Report on Observed Climate Trends and Projected Climate Change of the state-owned Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration(PAGASA). Luzon and Visayas will experience heavy and extreme rainfall during the southwest monsoon, making the wet season wetter.

This is bad news for Filipino farmers. “The agriculture sector is expected to suffer the most serious impacts of climate change, and food security, nutrition and livelihoods will be affected if we don’t act soon,” Julian Gonsalves, of the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, told SciDev.Net.

A World Bank report, Getting a Grip on Climate Change in the Philippines, has issued the same forecast. “Climate-related impacts are expected to reduce agricultural productivity in the Philippines,” the report said.

Rice, for instance, will be greatly affected by climate change. Rice yield reduction by up to 10% for each 1⁰C increase in night temperature, the weather bureau’s report pointed out. Studies have shown rice accounts for 41% of total caloric intake and 31% of total protein intake of Filipinos.

The Laguna-based International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) also has this observation: “Increasing carbon dioxide leads to increased photosynthesis and, potentially, more rice biomass. But concurrent increases in global temperature could also potentially limit rice harvests by increasing spikelet sterility.”

Corn, the other staple food of Filipinos, is not spared. The weather bureau’s report stated that corn yield will reduce by 1.7% should the day temperature goes up above 30⁰C under drought conditions.

These forecasts are consistent with what is happening already. About 5-7 percent decline in yield of major crops in the country has been attributed to climate change, according to the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development. “The yield reduction is caused by heat stress, decrease in sink formation, shortening of growing period, and increased maintenance for respiration,” it said.

A warmer climate causes the sea level to rise. The Philippines, whose coastline stretches 18,000 kilometers, is very vulnerable to sea level rise. In fact, the country ranks fourth in the Global Climate Risk Index as 15 provinces are susceptible to this climate change consequence.

The PAGASA report said that from 1993 to 2015, sea level “has risen in some parts by nearly double the global average rate.” The projected sea level rise under a high emissions scenario is 20 centimeters.

Water resources are also vulnerable to climate change. “In a warmer world, we will need more water – to drink and to irrigate crops,” said the London-based Panos Institute. “Water for agriculture is critical for food security,” points out Mark W. Rosegrant, a senior research fellow at the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute.

Water is very important in rice production. In his book, Water: The International Crisis, Robin Clark writes that a farmer needs 5,000 liters of water to produce one kilogram of rice. “Rice growing is a heavy consumer of water,” IRRI contends.

“The link between water and food is strong,” says Lester R. Brown, president of Washington, D.C.-based Earth Policy Institute. “We drink, in one form or another, nearly 4 liters of water per day. But the food we consume each day requires at least 2,000 liters to produce, 500 times as much.”

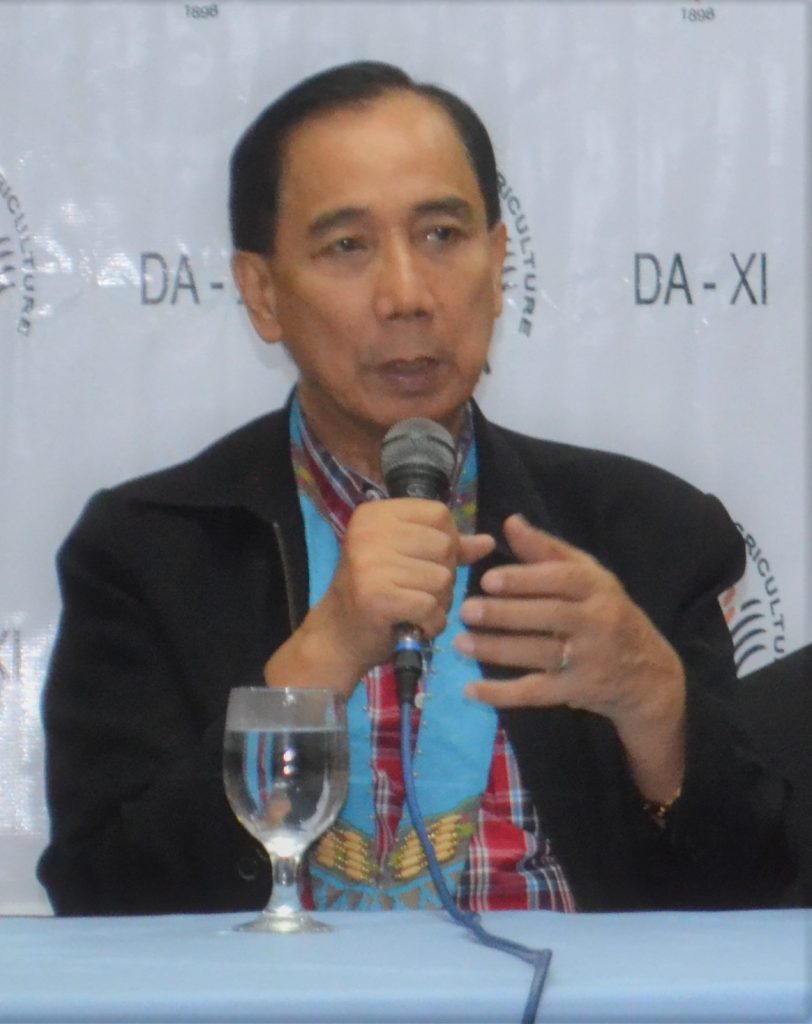

Dr. William Dar, the new secretary of Department of Agriculture, has included climate change as one of the nine myriad of challenges that can be blamed for the low farmer and fisherfolk income.

The other eight challenges are: low farm productivity, lack of labor, unaffordable and inaccessible credit, limited use of technology, limited farmland diversification, underdeveloped agri-manufacturing and export, severe deforestation/land degradation, and aging farmers and fisherfolk.

In his newly-published book, The Way Forward: Level Up Philippine Agriculture, Dr. Dar observed the Philippines is doing badly against climate change. What concerned him most are the smallholder farmers as they are “the most affected” when it comes to the effects of climate change.

Currently, smallholder farmers in the country are “adapting low input practices” and “improved practices.”

“Low input practices indicate the wider application of folk knowledge in farming and the use of non-hybrid seeds, resulting in very low yields,” Dr. Dar explained, and cited the yields of palay rice as a case in point.

“The average yield of palay in the Philippines is 4 to 5 metric tons per hectare but farmers that do not utilize improved planting materials have yields below 3 metric tons,” he wrote.

Dar also recommended “improved practices” to deal with the effects of climate change more effectively. The application of precision agriculture (PA) in which mechanization is a component as one of them.

“PA also overlaps some aspects of digital agriculture where information and communication technology, and the Internet of Things are applied to achieve higher productivity and profitability in growing crops and value adding,” Dr. Dar said.

Adapted germplasm is another aspect which does not only refer to hybrids but “also to biotech crops that have been designed to withstand the effects of climate change, primarily drought and flooding.”

“We are in trouble. We are in deep trouble with climate change,” said United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres during the opening of the 24th annual UN climate conference held in Poland some years back.

“It is hard to overstate the urgency of our situation,” Guterres pointed out. “Even as we witness devastating climate impacts causing havoc across the world, we are still not doing enough, nor moving fast enough, to prevent irreversible and catastrophic climate disruption.” – ###