Cirilo Estigoy, who died at the age of 92 in 2002, was very popular in his barrio when he was still alive. The reason: he survived after being bitten by a snake and became impervious to the venom after that.

As a rice farmer, Cirilo usually tended his farm. From time to time, he saw snakes coming out from his rice fields. But at one time, he was unwittingly bitten by a poisonous snake hiding the crop.

“My grandfather was bitten by a snake but survived because he knew what to do with the bite,” said Dr. Rodolfo Estigoy, who works with the Department of Agriculture, “He roasted his foot so the venom would come out. After that, he was already resistant to venom. He always told us this story when we were young.”

Cirilo was lucky. But not TJ Laurence of barangay Valencia in Ormoc City. According to an Inquirer report, the boy who was alone at home was bitten by a snake. It was not until two hours later that his parents arrived and learned what happened. The parents brought him to the health center but was advised to bring their son to a hospital.

“Upon arrival at the hospital, the father was told to get an anti-venom medicine from the city health office. It took a while since the anti-venom supply was kept at another hospital.

“The boy, who was still at emergency room, received a dose of anti-venom (three hours after he was bitten by the snake), but he died a few minutes later,” Elvie Roman Roa reported.

The Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) reports that about 3 million people are bitten by venomous snakes each year, with an estimated 81,000 to 138,000 deaths. There are also 400,000 survivors but most of them suffer from permanent disabilities and other aftereffects.

“Snakebites have always been included in the neglected tropical diseases throughout the world,” says Dr. Patrick Joseph G. Tiglao, board of director and secretary general of Philippine College of Emergency Medicine, Inc. “In the Philippines, the problem seems not to exist because of lack of awareness and lack of formal data.

The Philippine Statistics Authority states there are about 300 documented deaths annually from snakebites. “(The figure) does not include those undocumented and improperly documented ones,” Dr. Tiglao laments. “Snakebite incidences alone may reach to thousands if data are gathered throughout the Philippines. It’s just tip of the iceberg.”

One reason why total figure is hard to come by as most of those who die from it are from rural areas where reporting is almost nil. “Mainly because snakebites are happening in the outskirts, in the community where most of the patients would rather go to the traditional healers than consult with physicians,” Dr. Tiglao says.

“It is also bothersome to note that this is a disease of the poor,” he continues. “Those inflicted are farmers and mountain inhabitants who do not have access to immediate medical care. That’s the reason why it is not properly documented and underreported. It is not even part of the reportable cases. With lack of data or documentation, presto, the disease does not exist.”

According to Dr. Tiglao, snakebites occur mostly in rural areas as it is an occupational disease. “It affects mostly people from farming industry,” he says, adding that there are also fishermen who are bitten by sea snakes.

From July 1995 to July 2000, the Research Institute of Tropical Medicine (RITM) conducted a clinical profile of snakebite patients admitted at RITM. Majority of the 79 patients were male and rice farmers (except for 6 students and 1 preschooler). Locations of bite were mostly on the foot, occurring mostly at day time and usually unprovoked.

Results of the study conducted in India, where snakebites are also common, showed that 75% of snakebite victims die even before they reach the hospital “because there is no easy way to treat them in the field.” The research was published in the medical journal Clinical Case Reports.

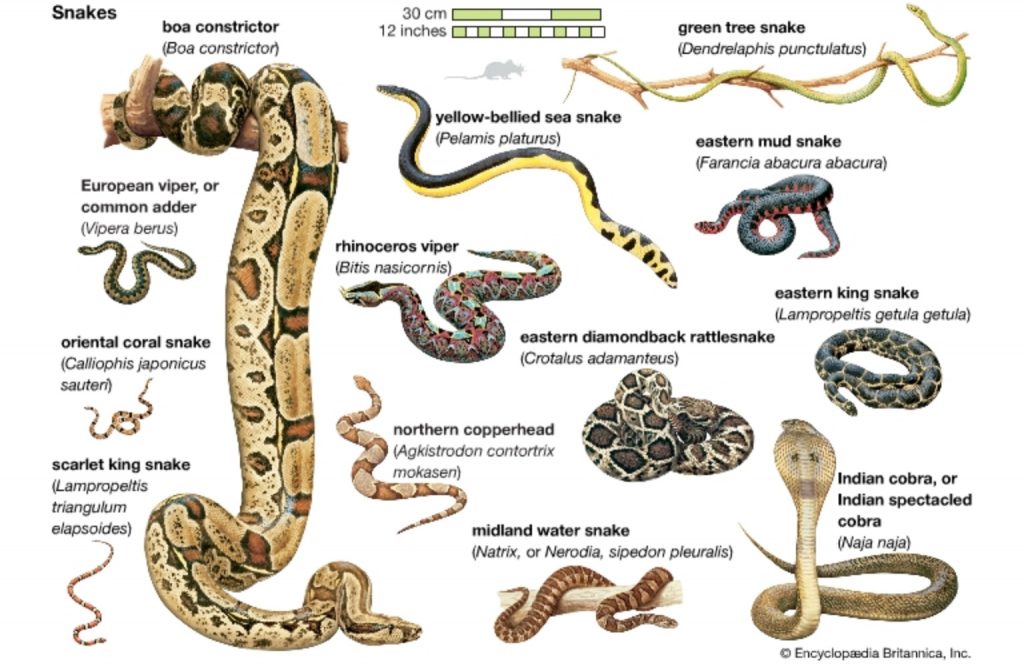

There are over 2,900 species of snakes and they can be found on every continent except Antarctica. The colloquial term “poisonous snake” is generally an incorrect label for snakes; the right term is “venomous snake.” A poison is inhaled or ingested, whereas venom is injected into its victim via fangs.

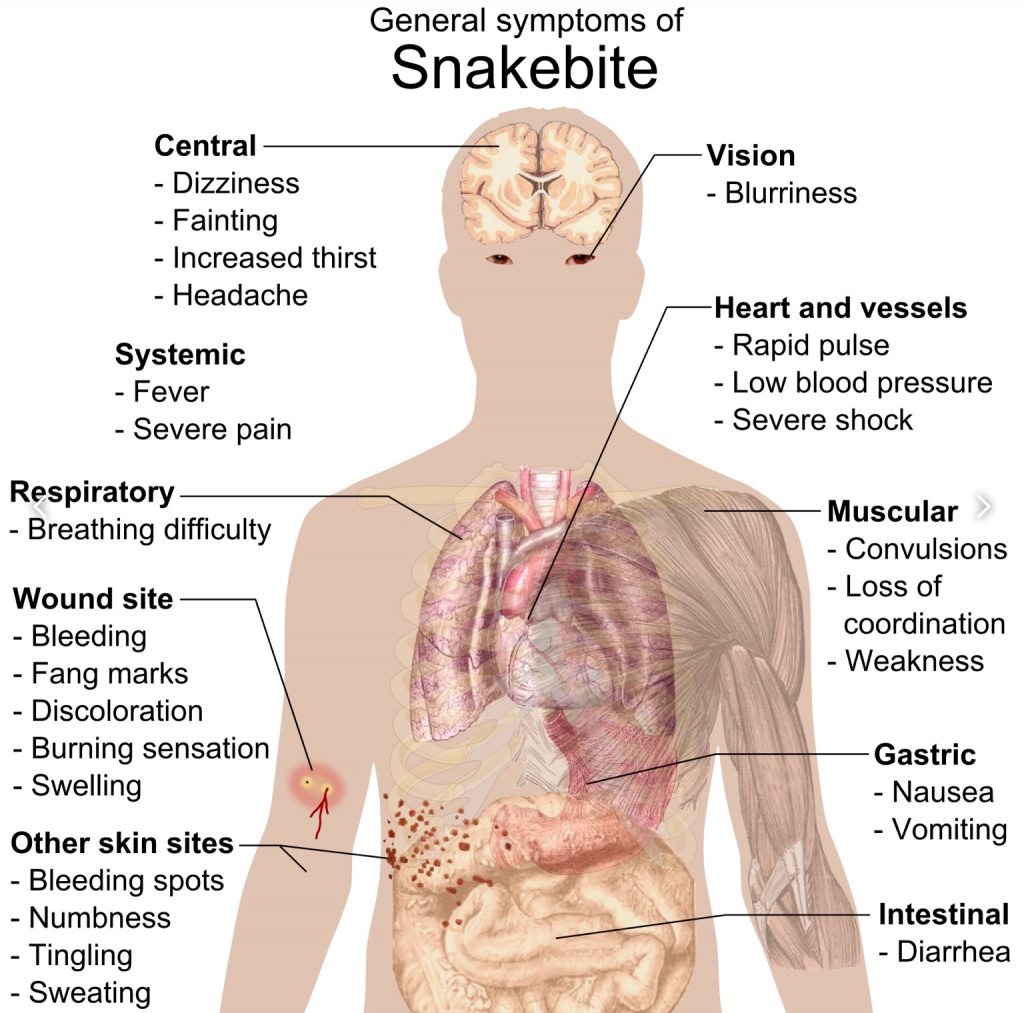

“Snake venoms are complex mixtures of proteins, and are stored in venom glands at the back of the head,” Wikipedia states. “In all venomous snakes, these glands open through ducts into grooved or hollow teeth in the upper jaw. These proteins can potentially be a mix of neurotoxins (which attack the nervous system), hemotoxins (which attack the circulatory system), cytotoxins, bungarotoxins, and many other toxins that affect the body in different ways. Almost all snake venom contains hyaluronidase, an enzyme that ensures rapid diffusion of the venom.”

Snakes exist since time immemorial. In fact, snake figures prominently in the Garden of Eden. For successfully convincing Eve to eat the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, God punished the snake.

In Exodus, snake made its appearance when Moses turned his staff into a frightening reptile. Moses also made a bronze snake on a pole that when looked at cured the people of bites from the snakes that plagued them in the desert. “Anyone who is bitten and looks at it shall live,” God told the prophet.

In medicine, snake is also used as a symbol. “Snakes are sometimes perceived as evil, but they are also perceived as medicine,” Hollywood actor Nicolas Cage was quoted as saying. “If you look at an ambulance, there’s the two snakes on the side of the car. The caduceus, or the staff of Hermes, there’s the two snakes going up it, which means that the venom can also be healing.”

Being a tropical country, the Philippines is blessed with the most ecologically unique and fascinating wildlife on the planet. The ecosystems on both land and sea are prime habitat for a large number of snake species. Most of them prefer to live in moist areas like rivers.

“The Philippines is home to some of the deadliest snakes in the world,” factsanddetails.com notes. “Out of a few hundred species, only a few are venomous. Most of them stay in rural areas, preying on small mammals such as rats and mice.”

While most of the snake species are harmless, the best advice is to treat all snakes as potentially dangerous. About 19 venomous snakes have been identified in the country, but they are classified into four categories: cobras, pit vipers, coral snakes and sea snakes.

Cobras are recognized by the intimidating hoods that extend on both sides of their heads. “Bites by cobras as immediately painful and tender to touch,” factsanddetails.com states. “When biting, these cobras tend to hold on and chew savagely. Specific symptoms of cobra envenomation include drowsiness, difficulty in speaking, drooling, blurred vision, shortness of breath, and loss of consciousness. These symptoms occur within one hour after the bite. Respiratory arrest can occur within minutes.”

In Samar, spitting cobras are common. They do so due to its nervous personality and when they are cornered. While the spray of venom (which can reach up to 2 meters) “is not especially harmful to intact skin, these cobras aim for the face and eyes, and it can cause blindness if not flushed and treated right away,” the website of Uncharted Philippines stated.

Pit vipers, on the other hand, are brightly-colored snakes which dwell in trees. One special feature about these types of snakes is that they give live birth to their young instead of laying eggs.

“Pit vipers possess a very sophisticated venom delivery system,” factsanddetails.com says. “Large tubular fangs are placed in the front of the mouth and they are hinged, allowing them to be folded back when not in use. Their venom is primarily hemotoxic and all of the lanced-headed vipers of the Philippines are capable of inflicting a dangerous bite.”

Although sea snakes are completely marine creatures, they are air breathers and must surface to breathe. “Generally, sea snakes are not aggressive,” factsanddetails.com says. “They are not thought to strike humans unless provoked, nor do they typically actively pursue swimming prey.”

There are some sea snakes whose venom is several times more toxic than the cobra’s. “Fortunately, only small amounts of venom are usually injected, so fatalities are rare,” factsanddetails.com says. “The most serious bites involve multiple serrated-edged lacerations which may result in death from respiratory, heart, or kidney failure.”

Coral snakes are different from sea snakes. “Coral snakes are identifiable by their marking, which consist of multicolor bands or stripes,” writes Alexander Harris for animals.mom.me. “Primary nocturnal, coral snakes avoid dry areas and populate scrub jungles and monsoon forests. They avoid human contact and are for the most part docile.”

The venom of snakes can be counterattacked by antivenom, a medication made from antibodies. “Each of the world’s 250 species of venomous snakes produces a unique cocktail of toxins that must be counteracted by a specific antivenom,” Science Magazine states.

Venoms, milked from snakes, are injected at low doses into animals, typically horses, to trigger an immune response. Antibodies from the animals’ blood are harvested, purified, and then used as antivenoms.

But the antivenoms are plagued by problems. “Antivenoms provide an imperfect solution for a number of reasons,” Science Daily points out. “Even if the snake has been identified and the corresponding antivenom exists, venomous bites are expensive, require refrigeration, and demand significant expertise to administer and manage.”

Antivenoms in some instances are unsafe. “This therapy can be lifesaving or limb-saving,” WebMd.com reminds. “Antivenom can occasionally also cause allergic reactions, however, or even anaphylactic shock, a life-threatening type of shock requiring immediate medical treatment with epinephrine and other medications.

“Antivenom can also cause serum sickness within 5-10 days of therapy,” it adds. “Serum sickness causes fevers, joint aches, swollen lymph nodes, and fatigue, but it is not life-threatening.”

Jociel M. Tecson, of the Good Shepherd Hospital of Panabo City, who recently attended a first aid course on snakebites, said only two hospitals in Davao has the supplies of antivenom: Southern Philippines Medical Center and Davao Regional Hospital in Tagum City.

“Both hospitals have 50 vials a year,” he said, adding that the supply is not enough. He cited the case of a 7-year-old girl who was bitten by a snake and was already on coma when she was brought to the SPMC. The attending physician, Dr. Ella Nogas-Perez, the center’s poison control institute director, immediately administered 10 vials of antivenom. Another 10 vials were followed up until she woke up. “How many vials more of antivenom are needed for a grown-up adult?” he asked.

Snakebites are here to stay. “Filipinos must be aware that snakebites are preventable,” says Dr. Tiglao, who is a member of the Remote Envenomation Consultancy Services (RECS), which do volunteer consultations for those inflicted with snakebites and also facilitates snakebites management. “It is also curable, when properly managed.”

According to Dr. Tiglao, the Philippines is home to three species of cobra “and all are treated with one antivenom produced by RITM.” He adds, “The antivenoms are limited to specific hospitals, mostly government institutions. For other species of snakes, we do not have antivenom for them. So, if you are bitten by a pit viper, no antivenom is available in the country.”

Dr. Tiglao’s final words: “Not knowing about snakebites won’t hurt you, but might kill you when you encountered one. Snakes are part of nature and we should learn to respect them in their habitat. Being responsible for our environment also means being responsible for ourselves.”

Photos taken from net