AURELIO A. PENA

AURELIO A. PENA is a Dabawenyo artist, replica painter, journalist and poet who once headed the Philippine News Agency (PNA)-Davao Bureau.

ONE COULD hardly notice the historic marker on one corner of a small triangular Children’s Park at the junction of Quezon Boulevard and Bonifacio streets in this bustling southern city.

Unless they read the marker, most residents and visitors will never know this was the spot 172 years ago where the Spanish trader Don Oyanguren y Cruz and his motley group of Spanish volunteer soldiers, ship crew, native settlers, etc. landed their armada of brigantine ships, sloops, and outrigger boats to prepare for an all-out assault against the proud, stubborn Moro warriors of Datu Mama Bago who vowed to die fighting to protect the riverside settlement called Dabaw against any invaders.

Selected passages from the book “Davao History” by the local historian Ernesto Corcino revealed the following details :

IT TOOK 14 months of a long sea voyage sailing on choppy seas from Manila, passing through the Visayan islands, towards the north-eastern tip of Surigao, passing along the Pacific coast of Mindanao, before the expedition led by Oyanguren , finally entered the big blue gulf, arriving at the tiny islet of Malipano beside Samal Island on March 1848. With him were around seventy people who all joined him in this dangerous journey to this thriving riverside settlement they call Dabaw.

Oyanguren’s two-mast sailing vessel known as a Brigantine, followed closely by smaller single-mast sailing ships known as Sloops, with cargo holds all filled with food supplies and armaments like muskets (single-shot guns), ammunitions, artillery (big cannons), gunpowder, etc, dropped anchor at Malipano islet, about ten kilometers across the sea of Davao Gulf to the tree-lined, swampy coast of mainland Davao.

Here, the Spanish trader was welcomed warmly by Datu Daupan, chief of the Samales tribe, who provided him information about the Moro settlement under the control of Datu Mama Bago at the mouth of Davao River. When the Samales tribe saw that Oyanguren’s group came to end the reign of oppression by Datu Mama Bago, they were excited and decided to join the fight against the Moro warrior.

Oyanguren had earlier accepted the offer and full support of the Spanish Governor General Narciso Claveria y Zaldua in Manila “to conquer and subdue” the entire Davao Gulf area —which was known at that time as “Taclooc Bay” — and expel the Moros there. The special deal hammered out with Claveria gave Oyanguren the “exclusive right” and full authority to govern the early Davao settlement for ten years, as well as the right to do business in Davao for six years after the conquest.

MANY YEARS earlier, there was a treaty in Mindanao, by which the Sultan Qudarat of Maguindanao ceded the entire Davao Gulf territory to Spanish control. Added as bonus to this treaty was an invitation to the Spaniards to open a trading post in Davao which encouraged many Spanish trading ships to head for Davao during that early period. Three years before Oyanguren made that historic voyage to Davao, a Spanish trading ship called “San Rufo” loaded with merchandise arrived at the Gulf and dropped anchor near the shores of the early Davao riverside settlement. The Spanish captain of the ship carried with him a “recommendation letter” from the Maguindanao sultan to the Davao chief Datu Mama Bago to receive the Spanish traders with “courtesy and respect” as personal friends of the Sultan.

Moro settlers along the coast pretended to respect the Sultan’s letter and welcomed the Spaniards, offering friendship and large quantities of wax to trade. Since the Moros of the early Dabaw settlement seemed so friendly to the Spanish visitors, most of the ship’s crew left the ship to go fishing at the Davao Gulf, while some went ashore in their small boats.

After noticing that most of the Spaniards were gone, a large band of Moros led by one Datu Ongay, climbed on board the Spanish ship pretending to offer and trade wax. While the remaining Spanish soldiers were cleaning their muskets and the ship crews were weighing the wax with Moro traders, they were suddenly overwhelmed in a violent bloody attack by the Moros. All the ship cargos were plundered and the entire ship put to the torch by the Moros, killing many of the Spaniards.

Maguindanao Sultan Qudarat, however, washed his hands of any blame and responsibility for the attack by the Moros on the trading ship San Rufo by telling the Spaniards that Datu Mama Bago and his warriors were not really his followers because they had also disobeyed his earlier instructions before, to receive Spanish traders as “friends of the Moros.”

THIS PROMPTED the Spanish authorities in Manila to cry for revenge and sounded the call for volunteer soldiers to go back and fight. The Spaniards were now bent on driving the Moro warriors away from the Dabaw riverside settlement. Faced by this prospect of conquering and controlling Davao, Oyanguren stepped forward and accepted the offer of the Spanish governor general Claveria to lead the risky expedition that will sail from Manila to Mindanao.

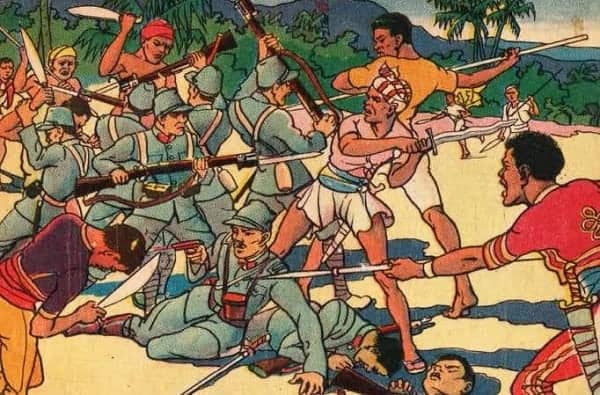

Backed by the tribal warriors of the Bagobos, the Samales and Mandaya tribal groups, Don Oyanguren and his Spanish volunteer fighters fought with the Moro warriors of Datu Mama Bago for the control of the riverside Dabaw settlement from April to June 1848.

The following passages from Corsino’s book described in detail the battle for Davao that broke out right after Oyanguren attempted to land several small boats and native outriggers loaded with Spanish volunteer soldiers and tribal warriors on the shores of Davao in an area we call today as “Trading” — marked by that historical marker at Quezon Boulevard.

FIERCE FIGHTING broke out on the riverbanks and swampy marshes along the mouth of the Davao River. For Don Oyanguren and his motley group of fighting men, it was not easy fighting off the Moro warriors in hit-and-run battles led by Datu Mama Bago—whose warriors were all well-armed with small canons called “lantakas” which can penetrate big ships and sink them.

The Moros had a large wooden fort or palisade on top of a hill beside the river (where the present University of Immaculate Conception (UIC) building stands next to Bankerohan public market). This fort, installed with lantakas, had an excellent view of the river all the way to the river’s mouth (“bucana”) which flows out to the sea of Davao Gulf.

Oyanguren’s three ships led by a brigantine and followed by the outrigger boats of Mandaya and Samales warriors attempted first to enter the Davao River to reach the fort on the hilltop, planning to bombard it with the brigantine’s big cannons.

This attempt to enter the river by Oyanguren’s ships was met by several volleys of lantaka cannon fire from the Moro warriors positioned on both sides of the riverbank. As lantaka rounds were punching holes into the attacking ships and smashing small boats into pieces, the Spaniards and their tribal allies were forced to retreat , turning back their ships and dragging with them a number of the dead and wounded.

Oyanguren was faced with the dilemma of how to attack the well-defended Moro fort with the ship’s big cannons. The Spanish trader figured out that the best way to hit the fort with their bigger cannons was to build a big dike across the nipa grove in the swamp. Using the dike as a shield, the Spaniards carried these heavy pieces of artillery on foot inland, through the swamps and try to get within firing range of the Moro fort.

Realizing what the Spaniards were doing, the Moro warriors sneaked up on the dike workers under cover of darkness, but were repelled in several hit-and-run encounters with Spanish soldiers guarding the construction of the earthen dike.

The big cannons were then positioned on the fortified dike, all aimed at the Moro fort on top of the hill beside the river. Knowing he could beat the Moro warriors this time, Oyanguren sent an emissary to the hilltop fort to demand the surrender of Datu Mama Bago who promptly turned it down. The Moro warriors defending the fort knew they cannot fight the Spanish invaders in an open battle because their lantaka cannons did not have enough supply of gun powder— but they were ready to fight to the very end.

As the Spanish soldiers and their tribal allies advanced on foot towards the hilltop fort, Moro warriors led by Datu Mama Bago himself led surprise ambushes and several hit-and-run attacks in the dark marshes and swamps, leaving behind many dead and wounded from both sides.

Big cannons set up on the improvised dike were fired, round after round, sending volleys of fireballs on the hilltop fort, hitting the bamboo houses and mosque inside the fort and razing the Moro settlement to the ground. In fierce hand to hand combat, attacking Spanish soldiers were hacked to death by the Moro’s deadly kampilan (big sword) while Moro warriors were felled by bullets from the muskets of the Spaniards— who were also cut down by attacking warriors in the dikes, bloody river banks and in the marshes and swamps of Davao.

Among the brave Moro warriors was Datu Malano who was feared by the Spanish invaders because he led many of the hit-and-run attacks and fought fiercely against the Spaniards. But on the third day of the battle, Datu Malano was hit by an artillery blast while leading his warriors to defend the Dabaw riverside settlement. He was killed by the blast while trying to defend the mosque, which was the target of artillery attack. Malano’s fall swiftly demoralized the Moro warriors. Instead of launching another wave of aggressive attack against the Spaniards, they were forced to retreat and merely tried to defend the riverside settlement.

In the midst of the battle, an artillery fireball hit the house of Datu Mama Bago, killing his first wife Bai Gomogonop. Tormented by his wife’s violent death and mounting losses in the battlefield, Datu Bago knew he could no longer stand up against the raging onslaught of the Spanish invaders and their tribal allies.

Under cover of darkness, Datu Bago split up his followers into several groups who then fled into the night. Accompanied by a small group of fleeing warriors, Datu Bago took a banca at the riverbank and paddled up the long winding Dabaw river to an area called Lapanday from where he escaped on foot all the way towards Tagum in the north.

ON THE MORNING of June 29, 1848, Oyanguren gathered all his men— Spanish volunteer soldiers, ship crew expedition members—for a thanksgiving mass in a makeshift bamboo chapel near a cluster of young acacia trees. The Spanish conqueror then dedicated the newly-captured Dabaw riverside settlement to Saint Peter the Apostle— on the exact spot where now stands the San Pedro Cathedral.

Standing across the cathedral today is a big imposing monument— a towering bronze sculpture showing both Moslems and Christians releasing white doves together— signifying their quests and commitments to peace, unity and understanding…

===============================

—- Sources and references : Letters of Fr. Mateo Gilbert SJ 1902 and selected portions of Ernesto Corcino’s book “Davao History” copyright 1998 Published by the Philippine Centennial Movement